Articoli correlati a Sarah Canary

When a strange white woman dressed in black wanders into a Chinese labor camp in the unsettled Pacific Northwest in 1873, Chin Ah Kin is appointed to escort her back from whence she came. Reprint.

Le informazioni nella sezione "Riassunto" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

Estratto. © Riproduzione autorizzata. Diritti riservati.:

The years after the American Civil War were characterized by excess, ornamented by cults and corruptions. Calamity Jane rode her horse through Indian country, standing on her head, her tangled hair loose along the horse's sides. Chang and Eng, P. T. Barnum's Siamese twins, hunted boar, fathered children, and drank like the gentlemen they were. The Fox sisters held seances and secretly cracked their toe knuckles to dissemble communication from the beyond. T. P. James, a psychic/mechanic in Vermont, channeled Charles Dickens, allowing him to complete his final book, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, posthumously. Big Jim Kinelly plotted the kidnap of Abraham Lincoln's body. Brigham Young married and Victoria Woodhull told everyone who was sleeping with whom. Football and lawn tennis had their first incarnations.

In 1871, strange events took place in the skies over the central and northern United States. Eyewitness accounts allude to spectacular meteor showers, ghostly lights, and, on the ground, a number of fires whose origins were unknown and whose behavior was, in some ways, disquietingly unfirelike.

In 1872, the residents of the asylum for the insane in Steilacoom, Washington, were thrown out of their beds by earthquakes resulting from volcanic activity in the Cascade Mountains. The event was so profound it cured three of the patients instantly. These cures were responsible for a brief and faddish detour in the care of the mentally ill known as shake treatments.

Across an ocean, in China, the Manchus prepared for the Year of the Rooster and the end of the female Regency. The power of the Dowager Empress shrank. The influence of the place eunuchs grew. Neither had much energy to spare for the Celestials dispersed abroad.

In 1873, in the fir forests below Tacoma, Washington, a white woman with short black hair and a torn black dress stumbled into a Chinese railway worker's camp.

Chapter One: The Year of the Rooster

To this World she returned.

But with a tinge of that--

A compound manner,

As a Sod

Espoused a Violet,

That chiefer to the Skies

Than to Himself, allied,

Dwelt hesitating, half of Dust

And half of Day, the Bride.

-Emily Dickinson, 1864

The railway workers were traveling from Seattle to Tenino on foot and had stopped, midday, to rest. They hadn't really made a camp, just a circle of baskets and blankets around a circle of damp dirt that Chin Ah Kin had cleared with his hands prior to building a fire. Chin was briefly alone, although in the distance to his left he could hear the companionable sounds of two men urinating.

It was midwinter, the tail end of the Year of the Monkey and just before noon. There was no snow, but the ground was wet with the morning's frost and the trees dripped. Underfoot, the fir needles were soggy and refused to snap when stepped upon, which might explain why Chin Ah Kin did not hear the woman approach. It was a mystery. She was just there suddenly, talking to someone, maybe to him, maybe to herself. Her speech had no meaning he could discern. Chin, whose mother had worked as a servant for German missionaries and later for a British family in the ceded area of Canton and briefly for a family of Mohammedans, had been surrounded by foreign languages all his life. People speaking a foreign tongue often appear more logical and intelligent than those who can be actually understood. It is inconceivable that extraordinary sounds should signify something trivial or mundane. But this woman's speech felt lunatic, and it was cold enough to give Chin the momentary illusion that her words had form inste

ad of meaning, were corporeal. He could see them, hovering about her open mouth.

In spite of the cold, the woman wore only a dress with crushed pannier and insubstantial leggings. This, too, was a mystery. Chin Ah Kin had been told that Puyallup Indians could sleep in the woods at night without blankets or shelter, but he had never heard this ability attributed to a white woman. Initially, he mistook her for a ghost.

He had been hoping for a ghost. Ghost women often appeared to men of his age, luring them away, entrapping them in seductions that might last for centuries. Such men returned to bewildering and alien landscapes. The trees would be the same, though larger; there the apple tree that grew in the corner of the yard, there the almond that once shaded the doorway. Trees are as close to immortality as the rest of us ever come. But the house would be gone, the people transformed; granddaughters into old women, daughters into the grass on their graves. Popular wisdom held that these men were lucky to have escaped at all, but Chin had his own opinions about this. Chin was a philosopher, his uncle said. Philosophers and running water always sought the easy way out. No more mining. No more working on the railroad. No need to send explanations or apologies to your parents back in China. But I was enchanted, he could always say later. Who was going to argue with this? Who would still be alive?

The ghost lover was so beautiful, she broke your heart just to look at her. She wore the faint perfume of your sweetest memories, a perfume that would be different to every man, depending on his province, the foods he liked, what his mother had used to wash her hair. The ghost lover dressed in clothes that were no longer fashionable. She seldom appeared in broad daylight, preferring shadows, and seldom faced you directly. There was something strange about her eyes, a light-swallowing flatness that always seemed to be an illusion no matter how closely you looked at her. Chin looked more closely at his apparition. She was the ugliest woman he could imagine. He revised his opinion. His second guess was that she was a prostitute.

To the best of his knowledge, he had never seen a white prostitute before. It was always possible that he had and not known it, of course, since the white men called prostitutes seamstresses and they called seamstresses seamstresses, too, and occasionally, like the famous Betsy Ross, revered them. It could get tricky. He recalled briefly the prostitute he had seen last year in eastern Washington. He and his uncle had been sluicing on the Columbia when a big-footed woman from Canton was taken through the mining camps. She wore the checkered scarf, so there was no mistaking her, and also a rope, one end tied around her waist, the other in the hands of the turtle man. While the man talked, the woman's head had drifted about her neck; her eyes rolled up in their sockets. She was ecstatic or she was very ill. She had a set of scars, little bird tracks, down the side of one cheek. Chin had wondered what would make such scars. "Very cheap," the turtle man assured them and then, to make

her more alluring, "She has just been with your father."

The woman in the forest gestured for Chin to come closer. Chin asked himself what could be gained by any intercourse with a white woman who had hair above her lip and also a nose that was long even by white standards. He looked away from her and into the trees, where his uncle was returning to camp holding two small birds that appeared to be domesticated doves. It was not at all clear that the woman had been gesturing to him, anyway.

"There is a small white woman with a large nose here," his uncle pointed out. Of course, he said it in Cantonese in case she understood English; it would not be so rude. "She is very ugly." Chin's uncle dropped one of the doves onto his blanket roll and shook the other; its head bobbed impotently on its neck. He took his knife from his boot and spread the bird on a tree stump fortuitously suited to this purpose. It was not a large stump, maybe two hands across, but it had many rings, each one fitting inside the next like a puzzle. People were like this too, Chin thought. A constant accumulation--each year, a little more experience, each year, another layer of wisdom. Old age was a state much to be envied.

Chin's uncle severed the bird's feet in a single motion. "So very sad. So tragic, really. The life of an ugly woman. If she does not leave soon, she will bring us all kinds of trouble. You must make her go away."

"She is looking for opium," Chin suggested, opium being the obvious antidote to the woman's state of overexcitement and the only thing he could imagine that would bring a white woman into a camp of Chinese men. He had smoked opium himself on several occasions and drunk it once. At no time had it left him in anything like this agitated condition. Poor ugly woman. He was overcome with sorrow at the situation. He moved to the other side of a tree, out of sight, and shouted at the crazy lady to go home. Her voice rose in response, an unpleasant, exultant clacking. It was possible she did not know that he was talking to her.

"You must be forceful," his uncle said. He had an unusually mobile face and one mole to the left side of his nose, which quivered distractingly when he spoke. He himself held forceful opinions, which he hinted had brought him powerful friends as well as potent enemies. He lived life inside the fist, belonging, or so he claimed, to the secret Society for the Broadening of Human Life and the Chinese Empire Reform Association as well. He hated the Dowager Empress, Tz'u-hsi, with a particularly forceful passion. "Overthrow the Ch'ing and restore the Ming," he might say, instead of "Good day," or "The Manchu Dowager contains twelve stinkpots that are inexplicable," but only if there were no strangers present.

He disapproved of Chin, whose philosophy of life was more flexible. Chin didn't care anymore who was Emperor in China. Chin could read American newspapers and would say anything anybody wanted to hear, even when no strangers were listeni...

Product Description:

In 1871, strange events took place in the skies over the central and northern United States. Eyewitness accounts allude to spectacular meteor showers, ghostly lights, and, on the ground, a number of fires whose origins were unknown and whose behavior was, in some ways, disquietingly unfirelike.

In 1872, the residents of the asylum for the insane in Steilacoom, Washington, were thrown out of their beds by earthquakes resulting from volcanic activity in the Cascade Mountains. The event was so profound it cured three of the patients instantly. These cures were responsible for a brief and faddish detour in the care of the mentally ill known as shake treatments.

Across an ocean, in China, the Manchus prepared for the Year of the Rooster and the end of the female Regency. The power of the Dowager Empress shrank. The influence of the place eunuchs grew. Neither had much energy to spare for the Celestials dispersed abroad.

In 1873, in the fir forests below Tacoma, Washington, a white woman with short black hair and a torn black dress stumbled into a Chinese railway worker's camp.

Chapter One: The Year of the Rooster

To this World she returned.

But with a tinge of that--

A compound manner,

As a Sod

Espoused a Violet,

That chiefer to the Skies

Than to Himself, allied,

Dwelt hesitating, half of Dust

And half of Day, the Bride.

-Emily Dickinson, 1864

The railway workers were traveling from Seattle to Tenino on foot and had stopped, midday, to rest. They hadn't really made a camp, just a circle of baskets and blankets around a circle of damp dirt that Chin Ah Kin had cleared with his hands prior to building a fire. Chin was briefly alone, although in the distance to his left he could hear the companionable sounds of two men urinating.

It was midwinter, the tail end of the Year of the Monkey and just before noon. There was no snow, but the ground was wet with the morning's frost and the trees dripped. Underfoot, the fir needles were soggy and refused to snap when stepped upon, which might explain why Chin Ah Kin did not hear the woman approach. It was a mystery. She was just there suddenly, talking to someone, maybe to him, maybe to herself. Her speech had no meaning he could discern. Chin, whose mother had worked as a servant for German missionaries and later for a British family in the ceded area of Canton and briefly for a family of Mohammedans, had been surrounded by foreign languages all his life. People speaking a foreign tongue often appear more logical and intelligent than those who can be actually understood. It is inconceivable that extraordinary sounds should signify something trivial or mundane. But this woman's speech felt lunatic, and it was cold enough to give Chin the momentary illusion that her words had form inste

ad of meaning, were corporeal. He could see them, hovering about her open mouth.

In spite of the cold, the woman wore only a dress with crushed pannier and insubstantial leggings. This, too, was a mystery. Chin Ah Kin had been told that Puyallup Indians could sleep in the woods at night without blankets or shelter, but he had never heard this ability attributed to a white woman. Initially, he mistook her for a ghost.

He had been hoping for a ghost. Ghost women often appeared to men of his age, luring them away, entrapping them in seductions that might last for centuries. Such men returned to bewildering and alien landscapes. The trees would be the same, though larger; there the apple tree that grew in the corner of the yard, there the almond that once shaded the doorway. Trees are as close to immortality as the rest of us ever come. But the house would be gone, the people transformed; granddaughters into old women, daughters into the grass on their graves. Popular wisdom held that these men were lucky to have escaped at all, but Chin had his own opinions about this. Chin was a philosopher, his uncle said. Philosophers and running water always sought the easy way out. No more mining. No more working on the railroad. No need to send explanations or apologies to your parents back in China. But I was enchanted, he could always say later. Who was going to argue with this? Who would still be alive?

The ghost lover was so beautiful, she broke your heart just to look at her. She wore the faint perfume of your sweetest memories, a perfume that would be different to every man, depending on his province, the foods he liked, what his mother had used to wash her hair. The ghost lover dressed in clothes that were no longer fashionable. She seldom appeared in broad daylight, preferring shadows, and seldom faced you directly. There was something strange about her eyes, a light-swallowing flatness that always seemed to be an illusion no matter how closely you looked at her. Chin looked more closely at his apparition. She was the ugliest woman he could imagine. He revised his opinion. His second guess was that she was a prostitute.

To the best of his knowledge, he had never seen a white prostitute before. It was always possible that he had and not known it, of course, since the white men called prostitutes seamstresses and they called seamstresses seamstresses, too, and occasionally, like the famous Betsy Ross, revered them. It could get tricky. He recalled briefly the prostitute he had seen last year in eastern Washington. He and his uncle had been sluicing on the Columbia when a big-footed woman from Canton was taken through the mining camps. She wore the checkered scarf, so there was no mistaking her, and also a rope, one end tied around her waist, the other in the hands of the turtle man. While the man talked, the woman's head had drifted about her neck; her eyes rolled up in their sockets. She was ecstatic or she was very ill. She had a set of scars, little bird tracks, down the side of one cheek. Chin had wondered what would make such scars. "Very cheap," the turtle man assured them and then, to make

her more alluring, "She has just been with your father."

The woman in the forest gestured for Chin to come closer. Chin asked himself what could be gained by any intercourse with a white woman who had hair above her lip and also a nose that was long even by white standards. He looked away from her and into the trees, where his uncle was returning to camp holding two small birds that appeared to be domesticated doves. It was not at all clear that the woman had been gesturing to him, anyway.

"There is a small white woman with a large nose here," his uncle pointed out. Of course, he said it in Cantonese in case she understood English; it would not be so rude. "She is very ugly." Chin's uncle dropped one of the doves onto his blanket roll and shook the other; its head bobbed impotently on its neck. He took his knife from his boot and spread the bird on a tree stump fortuitously suited to this purpose. It was not a large stump, maybe two hands across, but it had many rings, each one fitting inside the next like a puzzle. People were like this too, Chin thought. A constant accumulation--each year, a little more experience, each year, another layer of wisdom. Old age was a state much to be envied.

Chin's uncle severed the bird's feet in a single motion. "So very sad. So tragic, really. The life of an ugly woman. If she does not leave soon, she will bring us all kinds of trouble. You must make her go away."

"She is looking for opium," Chin suggested, opium being the obvious antidote to the woman's state of overexcitement and the only thing he could imagine that would bring a white woman into a camp of Chinese men. He had smoked opium himself on several occasions and drunk it once. At no time had it left him in anything like this agitated condition. Poor ugly woman. He was overcome with sorrow at the situation. He moved to the other side of a tree, out of sight, and shouted at the crazy lady to go home. Her voice rose in response, an unpleasant, exultant clacking. It was possible she did not know that he was talking to her.

"You must be forceful," his uncle said. He had an unusually mobile face and one mole to the left side of his nose, which quivered distractingly when he spoke. He himself held forceful opinions, which he hinted had brought him powerful friends as well as potent enemies. He lived life inside the fist, belonging, or so he claimed, to the secret Society for the Broadening of Human Life and the Chinese Empire Reform Association as well. He hated the Dowager Empress, Tz'u-hsi, with a particularly forceful passion. "Overthrow the Ch'ing and restore the Ming," he might say, instead of "Good day," or "The Manchu Dowager contains twelve stinkpots that are inexplicable," but only if there were no strangers present.

He disapproved of Chin, whose philosophy of life was more flexible. Chin didn't care anymore who was Emperor in China. Chin could read American newspapers and would say anything anybody wanted to hear, even when no strangers were listeni...

Book by Fowler Karen Joy

Le informazioni nella sezione "Su questo libro" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

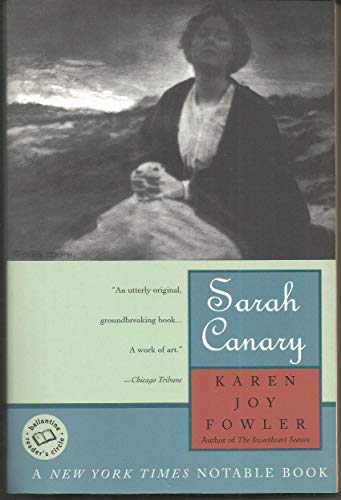

- EditoreBallantine Books

- Data di pubblicazione1998

- ISBN 10 0345416449

- ISBN 13 9780345416445

- RilegaturaCopertina flessibile

- Numero di pagine290

- Valutazione libreria

Compra nuovo

Scopri di più su questo articolo

EUR 71,19

Spese di spedizione:

EUR 3,79

In U.S.A.

I migliori risultati di ricerca su AbeBooks

SARAH CANARY (BALLANTINE READER'

Editore:

Ballantine Books

(1998)

ISBN 10: 0345416449

ISBN 13: 9780345416445

Nuovo

Brossura

Quantità: 1

Da:

Valutazione libreria

Descrizione libro Condizione: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.6. Codice articolo Q-0345416449

Compra nuovo

EUR 71,19

Convertire valuta