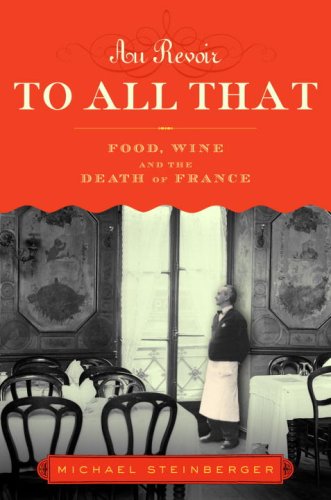

Articoli correlati a Au Revoir to All That: Food, Wine, and the Decline...

France is in a rut, and so is French cuisine. Twenty-five years ago it was hard to have a bad meal there; today it’s difficult to find a good one. An unmistakable whiff of decline emanates from its kitchens, and many believe that London, Spain, and New York are more exciting places to eat. Parisian bistros and brasseries are disappearing at an alarming rate; large segments of France’s wine industry are in crisis; many artisanal products are threatened with extinction. But astonishingly, business is good for McDonald’s: France has become its second-most profitable market in the world.

How this happened and what is being done to revive the gastronomic arts in France are the questions at the heart of this book. Steinberger meets top chefs, winemakers, farmers, bakers, and other artisans, interviews the head of McDonald’s Europe, marches down a Paris boulevard with "alter-globalization" activist José Bové, and breaks bread with the editorial director of the very powerful and secretive Michelin Guide. The result is a striking portrait of a cuisine and a country in transition.

Le informazioni nella sezione "Riassunto" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

On an uncomfortably warm September evening in 1999, I swapped my wife for a duck liver. The unplanned exchange took place at Au Crocodile, a Michelin three-star restaurant in the city of Strasbourg, in the Alsace-Lorraine region of France. We had gone to Crocodile for dinner and, at the urging of our waiter, had chosen for our main course one of Chef Emile Jung’s signature dishes, Foie de Canard et Écailles de Truffe en Croûte de Sel, Baeckeofe de Légumes. Baeckeofe is a traditional Alsatian stew made of potatoes, onions, carrots, leeks, and several different meats. Jung, possessed of that particular Gallic genius for transforming quotidian fare into high cuisine, served a version of baeckeofe in which the meats were replaced by an entire lobe of duck liver, which was bathed in a truffled bouillon with root vegetables and cooked in a sealed terrine. The seal was broken at the table, and as soon as the gorgeous pink-gray liver was lifted out of its crypt and the first, pungent whiff of black truffles came our way, I knew our palates were about to experience rapture. Sure enough, for the ten minutes or so that it took us to consume the dish, the only sounds we emitted were some barely suppressed grunts and moans. The baeckeofe was outrageously good — the liver a velvety, earthy, voluptuous mass, the bouillon an intensely flavored broth that flattered everything it touched.

We had just finished dessert when Jung, a beefy, jovial man who looked to be in his mid-fifties, appeared at our table. We thanked him profusely for the meal, and my wife, an editor for a food magazine, asked about some of the preparations. From the look on his face, he was smitten with her, and after enthusiastically fielding her questions, he invited her to tour the kitchen with him. “We’ll leave him here,” he said, pointing at me. As my wife got up from the table, Jung eyed her lasciviously and said, “You are a mango woman!” which I took to be a reference to her somewhat exotic looks (she is half-American, half-Japanese). She laughed nervously; I laughed heartily. As Jung squired her off to the kitchen, I leaned back in my chair and took a sip of Gewurztraminer.

By now, it was midnight, the dining room was almost empty, and the staff had begun discreetly tidying up. After some minutes had passed, Madame Jung, a lean woman with frosted blonde hair who oversaw the front of the restaurant, approached my table, wearing a put-upon smile which suggested this wasn’t the first time her husband had taken a young female guest to see his pots and pans. Perhaps hoping to commiserate, she asked me if everything was okay. “Bien sûr,” I immediately replied, with an enthusiasm that appeared to take her by surprise. I was in too much of a stupor to engage in a lengthy conversation, but had I been able to summon the words, I would have told her that her husband had just served me one of the finest dishes I’d ever eaten; that surrendering my wife (in a manner of speaking) was a small price to pay for such satisfaction; and that I’d have gladly waited at the table till daybreak if that’s what it took to fully convey my gratitude to Monsieur Jung.

In the end, I didn’t have to wait quite that long. After perhaps forty-five minutes, Jung returned my wife to the table. She came back bearing gifts: two bottles of the chef’s own late-harvest Tokay Pinot Gris and, curiously, a cold quail stuffed with foie gras, which had been wrapped in aluminum foil so that we could take it with us. We thanked him again for the memorable dinner and his generosity, and then he showed us to the door. There, I received a perfunctory handshake, while my wife got two drawn-out pecks, one to each cheek. She got two more out in front of the restaurant, and as we walked down the street toward our hotel, Jung joyfully shouted after her, “You are a mango woman!” his booming voice piercing the humid night air.

Early the next morning, driving from Strasbourg to Reims in a two-door Peugeot that felt as if it was about to come apart from metal fatigue, my wife and I made breakfast of the quail. We didn’t have utensils, so we passed it back and forth, ripping it apart with our hands and teeth. As we wound our way through the low, rolling hills of northeast France, silently putting the cold creature to an ignominious end, I couldn’t help but marvel at what had transpired. Where but in France could a plate of food set in motion a chain of events that would find you whimpering with ecstasy in the middle of a restaurant; giving the chef carte blanche to hit on your wife, to the evident dismay of his wife; and joyfully gorging yourself just after sunrise the next day on a bird bearing the liver of another bird, a gift bestowed on your wife by said chef as a token of his lust? The question answered itself: This sort of thing could surely only happen in France, and at that moment, not for the first time, I experienced the most overwhelming surge of affection for her.

I first went to France as a thirteen-year-old, in the company of my parents and my brother, and it was during this trip that I, like many other visitors there, experienced the Great Awakening — the moment at the table that changes entirely one’s relationship to food. It was a vegetable that administered the shock for me: Specifically, it was the baby peas (drowned in butter, of course) served at a nondescript hotel in the city of Blois, in the Loire Valley, that caused me to realize that food could be a source of gratification and not just a means of sustenance — that mealtime could be the highlight of the day, not simply a break from the day’s activities.

A few days later, while driving south to the Rhone Valley, my parents decided to splurge on lunch at a two-star restaurant called Au Chapon Fin, in the town of Thoissey, a few miles off the A6 in the Macon region. I didn’t know at the time that it was a restaurant with a long and illustrious history (among its claims to fame: It was where Albert Camus ate his last meal before the car crash that killed him in 1960), nor can I recollect many details of the meal. I remember having a pate to start, followed by a big piece of chicken, and that both were excellent, but that’s about it. However, I vividly recall being struck by the sumptuousness of the dining room. The tuxedoed staff, the thick white tablecloths, the monogrammed plates, the heavy silverware, the ornate ice buckets — it was the most elegant restaurant I’d ever seen. Every table was filled with impeccably attired, perfectly mannered French families. I hadn’t yet heard of Baudelaire, but this was my first experience of that particular state of bliss he described as luxe, calme, et volupté (richness, calm, and pleasure), and I found it enthralling.

Other trips to France followed, and in time, France became not just the place that fed me better than any other, but an emotional touchstone. In low moments, nothing lifted my mood like the thought of Paris — the thought of eating in Paris, that is. When I moved to Hong Kong in 1994, I found a cafe called DeliFrance (part of a local chain by the same name) that quickly became the site of my morning ritual; reading the International Herald Tribune over a watery cappuccino and a limp, greasy croissant, I imagined I was having breakfast in Paris, and the thought filled me with contentment. Most of the time, though, I was acutely aware that I was not in Paris. On several occasions, my comings and goings from Hong Kong’s airport coincided with the departure of Air France’s nightly flight to Paris. The sight of that 747 taxiing out to the runway always prompted the same thought: Lucky bastards.

In 1997, a few months after I moved back to the United States, the New Yorker published an article by Adam Gopnik asking, “Is There a Crisis in French Cooking?” The essay was vintage Gopnik — witty, well observed, and bristling with insight. Gopnik, then serving as the magazine’s Paris correspondent, suggested that French cuisine had lost its sizzle: It had become rigid, sentimental, impossibly expensive, and dull. The “muse of cooking,” as he put it, had moved on — to New York, San Francisco, Sydney, London. In these cities, the restaurants exuded a dynamism that was now increasingly hard to find in Paris. “All this,” wrote Gopnik, “makes a Francophile eating in Paris feel a little like a turn-of-the-century clergyman who has just read Robert Ingersoll: you try to keep the faith, but Doubts keep creeping in.”

I didn’t share those Doubts: To me, France remained the orbis terrarum of food, and nothing left me feeling more in love with life than a sensational meal in Paris. I refused to entertain the possibility that French cuisine had run aground; I didn’t see it then, and I still didn’t see it when Emile Jung took off with my wife two years later during that Lucullan evening at Au Crocodile. Sure, I knew that it was now pretty easy to find bad food in France if you went looking for it. I was aware, too, that France’s economic difficulties had made it brutally difficult for restaurants like Au Crocodile to keep the stoves running. In 1996, Pierre Gagnaire, a three-star chef in the industrial city of Saint-Etienne, near Lyon, had gone bankrupt, and the same fate had almost befallen another top chef, Marc Veyrat. I also recognized that I was perhaps prone to a certain psychophysical phenomenon, common among France lovers, whereby the mere act of dining on French soil seemed to enhance the flavor of things. Even so, as far as I was concerned, France remained the first nation of food, and anyone suggesting otherwise either was being willfully contrarian or was eating in the wrong places.

It was the swift and unexpected demise of Laduree just after the turn of the millennium that caused the first Doubts to cre...

Le informazioni nella sezione "Su questo libro" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

- EditoreDoubleday of Canada

- Data di pubblicazione2009

- ISBN 10 0385664729

- ISBN 13 9780385664721

- RilegaturaCopertina rigida

- Numero di pagine243

- Valutazione libreria

Spese di spedizione:

EUR 9,19

Da: Canada a: U.S.A.

I migliori risultati di ricerca su AbeBooks

Au Revoir to All That: Food, Wine, and the Decline of France

Descrizione libro Hardcover. Condizione: Good. 1st. Bargain book!. Codice articolo X007253

Au Revoir to All That: Food, Wine and the End of France

Descrizione libro Hardcover. Condizione: Very Good+. Condizione sovraccoperta: Very Good+, Not Price Clipped. Canadian First. First edition, first printing as evidenced by a complete number line from 1 to 10; minor edge wear; otherwise a solid, clean copy in collectable condition; appears to have been read only once. Book. Codice articolo 001969