Articoli correlati a Black Dog of Fate: A Memoir

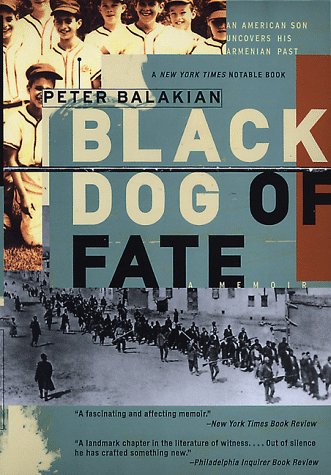

The first-born son of his generation, Peter Balakian grew up in a close, extended family, sheltered by 1950s and '60s New Jersey suburbia and immersed in an all-American boyhood defined by rock 'n' roll, adolescent pranks, and a passion for the New York Yankees that he shared with his beloved grandmother. But beneath this sunny world lay the dark specter of the trauma his family and ancestors had experienced--the Turkish government's extermination of more than a million Armenians in 1915, including many of Balakian's relatives, in the century's first genocide.

In elegant, moving prose, Black Dog of Fate charts Balakian's growth and personal awakening to the facts of his family's history and the horrifying aftermath of the Turkish government's continued campaign to cover up one of the worst crimes ever committed against humanity. In unearthing the secrets of a family's past and how they affect its present, Black Dog of Fate gives fresh meaning to the story of what it means to be an American.

In elegant, moving prose, Black Dog of Fate charts Balakian's growth and personal awakening to the facts of his family's history and the horrifying aftermath of the Turkish government's continued campaign to cover up one of the worst crimes ever committed against humanity. In unearthing the secrets of a family's past and how they affect its present, Black Dog of Fate gives fresh meaning to the story of what it means to be an American.

Le informazioni nella sezione "Riassunto" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

L'autore:

Peter Balakian is professor of English at Colgate University and the author of four books of poems, most recently Dyer's Thistle. He lives in Hamilton, New York.

Estratto. © Riproduzione autorizzata. Diritti riservati.:

An Armenian Jew in Suburbia

We always lingered over dinner after church on Sunday afternoon. In summer we dined on the brick patio in the backyard under the shade of the maple. A plastic tablecloth over the picnic table. The smell of charred lamb. A silver serving dish with some leftover shish kebab and seared vegetables for those whose appetite might reemerge after a while of talking. The pink-and-white azaleas and the little lavender bouquets of rhododendron petals lushly hemming us in. Sunday was family day. On Sunday we seemed more Armenian. Some assortment of relatives--my grandmother, aunts, cousins, uncles-always would be there.

On Sundays I felt like I watched my family as if I were watching a play. My mother passes a tray of bereks, triangles of filo filled with sharp cheese and parsley, and Auntie Gladys passes a large bowl of ice in which float black olives and radishes cut into rose shapes. Everyone sits on lawn chairs and chaise lounges. A moment later, my mother opens the sliding glass door carrying a tray of highball glasses filled with tahn, a drink of yogurt and water poured over ice and mint leaves. In a white silk blouse and a dark skirt with an apron tied around her waist, my mother is formal and informal, at once decorous and casually suburban, with dark wavy hair cut short against her fair, freckled skin. She is never sitting down but poking and prodding at the food, passing around plates and silverware, and delegating small responsibilities to everyone to make sure we are all within earshot of her voice. At the grill built into the side of the brick chimney my father is fanning the coals, and in the kitchen my mother is seeing the lamb through its last stages.

Since Saturday night the shish kebab has been marinating in a large terra-cotta bowl with slices of onion, coriander, paprika, some crude olive oil, some red wine. As the oil soaks into the paprika, making a rosy hue on the lamb and the pearly crescents of onions and flecks of black pepper and allspice, the whole bowl glistens. Cubed and trimmed of fat, spring lamb is soft and a deep brick color as you glide it up the skewer with chunks of green pepper, Spanish onions, and Jersey Beefsteak tomatoes before it goes over the white coals.

When the vegetables are charred and the lamb slides off the skewers, my father fills the large silver bowl. In a blue-and-white painted dish is a pyramid of pilaf decorated with dried fruits and nuts; there is a basket of bakery rolls and small glass dishes piled with pickled vegetables called tourshi. I sit with my hands on my cheeks, scowling and hungry. The only thing that pleases me is the food--its wonderful colors and many fragrances. From around the block I can hear cap guns and my friends playing ball and tag. All want is to eat in a simple five minutes and get the hell out of this extended ring of adults, but the very idea is impossible because this is an immovable feast, an unquestioned reality of our Balakian Sunday ritual. And I might as well have tar on my butt because I'm stuck here for the day. After the tahn and bereks and shish kebab, there will be paklava or kadayif, some melon and grapes and a soft hunk of fresh white cheese, and finally, some cardamom sweet coffee in small porcelain cups; and for the venturesome members of the family, a sip of French cognac.

If Auntie Anna was with us (as she often was), she would proclaim, not too long after tahn was served, that suburbia would be the ruin of America, and she was not subtle about letting us know that it would be the ruin of us, too. My aunt Anna Balakian was my father's oldest sister, and although she was married, she used her maiden name professionally, which was unusual for a woman in the 1950s. She was a professor at NYU and her books on French poetry bore the name Balakian on the book jacket

Auntie Anna spoke with such opinionated emotion that she could cast fallout on the conviviality of the moment "The whole idea of su-burr-bi-aa is wrong"--she liked to linger on a vowel so that the depth of her opinion was inseparable from each word. "This is how the bourgeoisie will triumph," she said, as my mother grew indignant. "There's more community and goodwill here than anywhere in America, Anna, or anywhere in the world, for that matter," she glowered back. "You're lost here," Auntie Anna said, and made it clear that we had sold our souls to a barbarous society that didn't know the difference between Monet and Donald Duck, Mallarme and Michener. We would become just like everybody else--a thin slice of yellow plastic cheese in the long, soft loaf of Velveeta that was America. Before my mother could erupt, my father interrupted with some comment about how well the kebabs had come out, and members of each side of the family tried to disentangle the two women by urging them to get the dishes and platters and bowls of food around the table. "Peter needs some more 7-Up," my grandmother said loudly to my mother, "come on, hurry up, hurry up."

I remember a lot of conversation in the family about the suburbs in those days, especially in 1960, after we had moved to Tenafly. A book called The Split-Level Trap had come out that year written by Dick Gordon, a psychiatrist, and his wife, Kitty, who lived a few blocks away and were friends of my parents. The Split-Level Trap, which bore the dedication "To the people of Bergen County, New Jersey," was an insider's guide to the moral decay of suburban life--divorce, alcoholism, adultery, juvenile delinquency--and it prophesied doom. Because my parents knew that the Gordons' field work had been done in Tenafly and other neighboring towns I began to wonder, as I listened to my aunt and mother fight it out, why my parents settled here. My aunt's rants against the suburbs were unsettling. I would watch my mother bristle with anger at Auntie Anna, and my aunt staring with fierce disapproval at my father, seeming to me to say, Why did you marry her and come to these suburbs?

Almost every part of Bergen County was an easy commute to Manhattan, but not every part was new suburbia. Our first house was a two-story brick and clapboard built in the thirties. It straddled the sloped corner of West Englewood Avenue and Dickerson Road in Teaneck. Our part of Teaneck was mostly brick and clapboard or stucco and plank, Tudor revival, dating from the decades between the wars when Teaneck had become a fashionable suburb. In 1953 my father set an iron lamppost into the front lawn and hung a sign announcing his medical practice.

The lawns of Teaneck were well manicured, thick and green and edged with privet, forsythia, or hydrangea. My father and our neighbors compulsively yanked and dug and pulled and poisoned weeds out of the cracks between the large concrete blocks that made up the sidewalks. In the driveways of Dickerson Road were Fords and Chevys, some Buicks and Oldsmobiles. I remember Mr. Goldfischer's Caddy, a white '56 with chrome that shined like the bullet noses of the rockets I gazed at in LIFE magazine. Every morning I stared out my bedroom window at the driveways separated by a strip of grass and at the Goldfischer Cadillac, which dwarfed the gray '54 Olds my father and mother shared, the seats of which gave off the sour residue of regurgitated milk and infant formula and "a faint uriniferous odor," as my father called it.

Dickerson Road was Jewish, and our neighbors were Blumenthal, Cohen, Berg, Berkowitz, Goldfischer, Oshinski, and Liebowitz--Jews who had moved up from Union City or Brooklyn after World War II. I spent half of my early childhood wanting to be Jewish, in Mark Blumenthal's finished basement with its paneled walls, fluorescent ceiling lights, and Ping-Pong table. On that dank floor with its loose linoleum tiles we flipped baseball cards and sat in front of a small RCA television to watch the Yankees. We played with toys made by Remco and Ideal. A miniature Cape Canaveral, with rockets and missiles, launching pads, and beautifully drawn control panels, was our favorite.

Around four o'clock Mrs. Blumenthal would call us to the kitchen for a rugulach or a cheese Danish and cream soda. Sitting at the red linoleum counter with its chrome edging, I smelled the kitchen filling up with the richness of corned beef boiling in a big aluminum pot on the stove, where it seemed to float in a strange gray scum of fat and bay leaves. I stared at the piled-high white bags from the bakery and the small brown ones from the A & P, oilstained paper bags of bagels, salt sticks, Danish. I thought the jars of herring and sour cream were jars of marshmallow candy, until I asked for some one day and found myself forcing the slimy fish hunks down my throat. I gazed at the mason jars of yellowish jelly full of gefilte fish and the almost patriotic stack of red, white, and blue boxes of matzoh on which Hebrew letters seemed to climb like spiders. Once a week a Beverages By Hammer truck pulled up to Mark's house and a man in a white uniform disappeared into the Blumenthals' basement with a crate of twelve turquoise spritzer bottles and came out with a crate of empties.

On Saturday mornings I watched from our window with envy as my friends walked with their parents in procession, family by family, down Dickerson Road on their way to schul. I wanted to join the men and boys in their black and white yarmulkes and their silk t...

We always lingered over dinner after church on Sunday afternoon. In summer we dined on the brick patio in the backyard under the shade of the maple. A plastic tablecloth over the picnic table. The smell of charred lamb. A silver serving dish with some leftover shish kebab and seared vegetables for those whose appetite might reemerge after a while of talking. The pink-and-white azaleas and the little lavender bouquets of rhododendron petals lushly hemming us in. Sunday was family day. On Sunday we seemed more Armenian. Some assortment of relatives--my grandmother, aunts, cousins, uncles-always would be there.

On Sundays I felt like I watched my family as if I were watching a play. My mother passes a tray of bereks, triangles of filo filled with sharp cheese and parsley, and Auntie Gladys passes a large bowl of ice in which float black olives and radishes cut into rose shapes. Everyone sits on lawn chairs and chaise lounges. A moment later, my mother opens the sliding glass door carrying a tray of highball glasses filled with tahn, a drink of yogurt and water poured over ice and mint leaves. In a white silk blouse and a dark skirt with an apron tied around her waist, my mother is formal and informal, at once decorous and casually suburban, with dark wavy hair cut short against her fair, freckled skin. She is never sitting down but poking and prodding at the food, passing around plates and silverware, and delegating small responsibilities to everyone to make sure we are all within earshot of her voice. At the grill built into the side of the brick chimney my father is fanning the coals, and in the kitchen my mother is seeing the lamb through its last stages.

Since Saturday night the shish kebab has been marinating in a large terra-cotta bowl with slices of onion, coriander, paprika, some crude olive oil, some red wine. As the oil soaks into the paprika, making a rosy hue on the lamb and the pearly crescents of onions and flecks of black pepper and allspice, the whole bowl glistens. Cubed and trimmed of fat, spring lamb is soft and a deep brick color as you glide it up the skewer with chunks of green pepper, Spanish onions, and Jersey Beefsteak tomatoes before it goes over the white coals.

When the vegetables are charred and the lamb slides off the skewers, my father fills the large silver bowl. In a blue-and-white painted dish is a pyramid of pilaf decorated with dried fruits and nuts; there is a basket of bakery rolls and small glass dishes piled with pickled vegetables called tourshi. I sit with my hands on my cheeks, scowling and hungry. The only thing that pleases me is the food--its wonderful colors and many fragrances. From around the block I can hear cap guns and my friends playing ball and tag. All want is to eat in a simple five minutes and get the hell out of this extended ring of adults, but the very idea is impossible because this is an immovable feast, an unquestioned reality of our Balakian Sunday ritual. And I might as well have tar on my butt because I'm stuck here for the day. After the tahn and bereks and shish kebab, there will be paklava or kadayif, some melon and grapes and a soft hunk of fresh white cheese, and finally, some cardamom sweet coffee in small porcelain cups; and for the venturesome members of the family, a sip of French cognac.

If Auntie Anna was with us (as she often was), she would proclaim, not too long after tahn was served, that suburbia would be the ruin of America, and she was not subtle about letting us know that it would be the ruin of us, too. My aunt Anna Balakian was my father's oldest sister, and although she was married, she used her maiden name professionally, which was unusual for a woman in the 1950s. She was a professor at NYU and her books on French poetry bore the name Balakian on the book jacket

Auntie Anna spoke with such opinionated emotion that she could cast fallout on the conviviality of the moment "The whole idea of su-burr-bi-aa is wrong"--she liked to linger on a vowel so that the depth of her opinion was inseparable from each word. "This is how the bourgeoisie will triumph," she said, as my mother grew indignant. "There's more community and goodwill here than anywhere in America, Anna, or anywhere in the world, for that matter," she glowered back. "You're lost here," Auntie Anna said, and made it clear that we had sold our souls to a barbarous society that didn't know the difference between Monet and Donald Duck, Mallarme and Michener. We would become just like everybody else--a thin slice of yellow plastic cheese in the long, soft loaf of Velveeta that was America. Before my mother could erupt, my father interrupted with some comment about how well the kebabs had come out, and members of each side of the family tried to disentangle the two women by urging them to get the dishes and platters and bowls of food around the table. "Peter needs some more 7-Up," my grandmother said loudly to my mother, "come on, hurry up, hurry up."

I remember a lot of conversation in the family about the suburbs in those days, especially in 1960, after we had moved to Tenafly. A book called The Split-Level Trap had come out that year written by Dick Gordon, a psychiatrist, and his wife, Kitty, who lived a few blocks away and were friends of my parents. The Split-Level Trap, which bore the dedication "To the people of Bergen County, New Jersey," was an insider's guide to the moral decay of suburban life--divorce, alcoholism, adultery, juvenile delinquency--and it prophesied doom. Because my parents knew that the Gordons' field work had been done in Tenafly and other neighboring towns I began to wonder, as I listened to my aunt and mother fight it out, why my parents settled here. My aunt's rants against the suburbs were unsettling. I would watch my mother bristle with anger at Auntie Anna, and my aunt staring with fierce disapproval at my father, seeming to me to say, Why did you marry her and come to these suburbs?

Almost every part of Bergen County was an easy commute to Manhattan, but not every part was new suburbia. Our first house was a two-story brick and clapboard built in the thirties. It straddled the sloped corner of West Englewood Avenue and Dickerson Road in Teaneck. Our part of Teaneck was mostly brick and clapboard or stucco and plank, Tudor revival, dating from the decades between the wars when Teaneck had become a fashionable suburb. In 1953 my father set an iron lamppost into the front lawn and hung a sign announcing his medical practice.

The lawns of Teaneck were well manicured, thick and green and edged with privet, forsythia, or hydrangea. My father and our neighbors compulsively yanked and dug and pulled and poisoned weeds out of the cracks between the large concrete blocks that made up the sidewalks. In the driveways of Dickerson Road were Fords and Chevys, some Buicks and Oldsmobiles. I remember Mr. Goldfischer's Caddy, a white '56 with chrome that shined like the bullet noses of the rockets I gazed at in LIFE magazine. Every morning I stared out my bedroom window at the driveways separated by a strip of grass and at the Goldfischer Cadillac, which dwarfed the gray '54 Olds my father and mother shared, the seats of which gave off the sour residue of regurgitated milk and infant formula and "a faint uriniferous odor," as my father called it.

Dickerson Road was Jewish, and our neighbors were Blumenthal, Cohen, Berg, Berkowitz, Goldfischer, Oshinski, and Liebowitz--Jews who had moved up from Union City or Brooklyn after World War II. I spent half of my early childhood wanting to be Jewish, in Mark Blumenthal's finished basement with its paneled walls, fluorescent ceiling lights, and Ping-Pong table. On that dank floor with its loose linoleum tiles we flipped baseball cards and sat in front of a small RCA television to watch the Yankees. We played with toys made by Remco and Ideal. A miniature Cape Canaveral, with rockets and missiles, launching pads, and beautifully drawn control panels, was our favorite.

Around four o'clock Mrs. Blumenthal would call us to the kitchen for a rugulach or a cheese Danish and cream soda. Sitting at the red linoleum counter with its chrome edging, I smelled the kitchen filling up with the richness of corned beef boiling in a big aluminum pot on the stove, where it seemed to float in a strange gray scum of fat and bay leaves. I stared at the piled-high white bags from the bakery and the small brown ones from the A & P, oilstained paper bags of bagels, salt sticks, Danish. I thought the jars of herring and sour cream were jars of marshmallow candy, until I asked for some one day and found myself forcing the slimy fish hunks down my throat. I gazed at the mason jars of yellowish jelly full of gefilte fish and the almost patriotic stack of red, white, and blue boxes of matzoh on which Hebrew letters seemed to climb like spiders. Once a week a Beverages By Hammer truck pulled up to Mark's house and a man in a white uniform disappeared into the Blumenthals' basement with a crate of twelve turquoise spritzer bottles and came out with a crate of empties.

On Saturday mornings I watched from our window with envy as my friends walked with their parents in procession, family by family, down Dickerson Road on their way to schul. I wanted to join the men and boys in their black and white yarmulkes and their silk t...

Le informazioni nella sezione "Su questo libro" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

- EditoreBroadway Books

- Data di pubblicazione1998

- ISBN 10 0767902548

- ISBN 13 9780767902540

- RilegaturaCopertina flessibile

- Numero di pagine3

- Valutazione libreria

Compra nuovo

Scopri di più su questo articolo

EUR 17,78

Spese di spedizione:

GRATIS

In U.S.A.

I migliori risultati di ricerca su AbeBooks

Black Dog of Fate: An American Son Uncovers His Armenian Past

Da:

Valutazione libreria

Descrizione libro paperback. Condizione: New. Codice articolo 0767902548-11-28936384

Compra nuovo

EUR 17,78

Convertire valuta

Black Dog of Fate: An American Son Uncovers His Armenian Past

Da:

Valutazione libreria

Descrizione libro Paperback. Condizione: New. Codice articolo 180614037

Compra nuovo

EUR 19,00

Convertire valuta

BLACK DOG OF FATE: AN AMERICAN S

Da:

Valutazione libreria

Descrizione libro Condizione: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.6. Codice articolo Q-0767902548

Compra nuovo

EUR 70,73

Convertire valuta