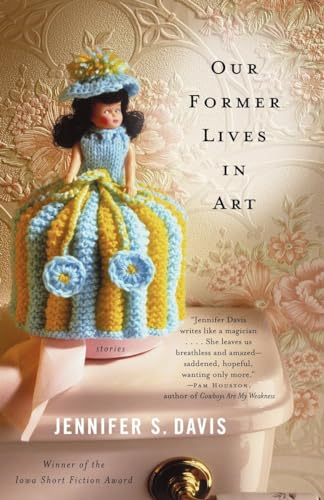

Articoli correlati a Our Former Lives in Art: Stories

A new compilation of short fiction by the award-winning author of Her Kind of Want journeys into the heart of the American Deep South to explore transcendant moments in the lives of ordinary people, from a man who stays beside the scene of a fatal car accident to share the final moments of a stranger's life, to a woman who befriends her lover's ailing wife. Original. 15,000 first printing.

Le informazioni nella sezione "Riassunto" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

L'autore:

Jennifer S. Davis is the author of Our Former Lives in Art and Her Kind of Want, which won the 2002 Iowa Award for Short Fiction. Her fiction has appeared in Grand Street, Oxford American, The Paris Review, and One Story. She lives in Colorado.

Estratto. © Riproduzione autorizzata. Diritti riservati.:

giving up the ghost

“Look, Frank, trick-or-treaters,” Carrie said, breaking the silence of the last half hour. “What are they doing all the way out here?”

“Here” was a country back road, eastern Alabama. Halloween, 1980.

“Those aren’t trick-or-treaters,” Frank said, easing the truck onto the sandy shoulder of the road. Up ahead, flipped on its side, half on the shoulder and half in the ditch, was a red-and-white-striped GMC Jimmy, one taillight blinking off and on, a maniacal, fluttering eye. Behind them, perhaps twenty feet, a knot of people huddled on the side of the road, not moving.

“Maybe we should drive on to the bait shop,” Frank said. “Call the police from the pay phone.” He had heard stories of people faking accidents in order to rob or rape unsuspecting Good Samaritans, and he couldn’t help but wonder if this was it, the night a knife slid across his throat or, worse, Carrie’s. The night everything was written out for them. The next morning, a work crew or a vagrant searching for aluminum cans would find their naked bodies on the side of the road, half-covered in wet pine needles, red clay.

“What’s your problem?” Carrie snapped. She opened her door, slid from the truck. “They might be hurt. Don’t just sit there.”

The first thing he noticed when he opened his own door was the smell, hovering and sweet, like just bloomed honeysuckles. That mixed with gasoline and burnt rubber.

“Are y’all all right?” Carrie half yelled at the still unmoving knot behind them, but she stayed close to the truck.

A man, maybe forty, with pulpy, torn lips, finally loped over, extending his hand to Frank in a strange semblance of formality. He had hair cropped so short it had no color, light eyes to match. He wore an unbuttoned Hawaiian covered with little monkeys surfing. Behind him trailed a young woman and a small girl, just past toddler. Both of their faces were pretty banged up. They rushed toward Carrie as though they knew her, began clutching at her arms in a panic until Carrie awkwardly embraced them.

“You’re the third car to come through here,” the man said, grinding the heels of his boots into the grainy road. “No one else would stop. No one. Who could see two hurt girls and keep going?” He tugged a hand through his short hair, revealing a bloody forehead. “I just don’t get it anymore, man. The big IT. You know what I mean?” He began crying, heaving gasps that horrified Frank. The man was shit-faced.

The woman had two-toned hair the yellow and copper of poor white, and she wailed in response, pressed her face against Carrie’s leather jacket. “I think they’re more scared than hurt,” Carrie said to no one in particular.

When the man reached for his wife, she pulled away. “My face, you idiot.” Her fingers moved over her cheeks as if she could piece it back together. “I’ve told you a thousand times. A thousand. Slow. Down.” The little girl clamped her eyes shut and didn’t make a sound. She wore a striped leotard, one foot bare, the other in a tiny ballet slipper, the remnants of her Halloween costume, a bumblebee.

“That car flew out of fucking nowhere,” the man said, suddenly angry. When he yelled, he sprayed blood instead of spit. He slammed a fist into his palm. “Nowhere.” His wife and kid tried to burrow holes into Carrie with their faces; they seemed familiar with his anger.

“What car?” Frank said. He’d assumed that it was a one-car accident, a drunk man overcompensating for veering off the road, something anyone could do, including Frank, who’d had a beer or two himself that night.

The man pointed behind them, into the fringe of woods off the oncoming lane.

“You checked it out?” Frank asked. The man stared at his boots, shook his head no. The woman began whimpering, soft and wet.

Frank looked to where the man had pointed. There, some fifty feet away, as bright as the harvest moon that lit the night, was a yellow Camaro, its front crushed against an oak like crumpled paper. Glass and bits of metal glittered against the asphalt. There was no reasonable explanation for how he could have not noticed it until that moment, and he could hear the refrain Carrie had been saying lately: You only see what you want to see, Frank. That’s your problem.

“You stay here,” Frank said to Carrie. “Wave anyone down who passes. Ask if they have a CB radio.”

It’s strange, but on his walk over to the Camaro, this was what he thought: What a lovely night! How could anything so violent happen on such a night? It was still and pleasant, warm for late October, and if he tilted his head back, he could see nothing but blue-black and stars. When he approached the car, he saw a teenage girl in a black leather dress, the bottom half of her body still in the driver’s seat, her trunk slung out the opened door into the thick brush, her long blond hair tangled with debris, her face pale and still as the night. In such a dramatic position, she was bizarrely beautiful.

The girl looked dead, but to be sure, he knelt, placed his finger against her neck for a pulse. Her skin felt silky, soft. From the looks of her, she was the kind to pamper it, to spread creamy lotion over her neck, arms, elbows, chest. He held his finger there for a full minute before he felt a flicker, soft as eyelashes.

Frank cannot help but ask himself now, Should he have pulled her from the car? Would it have somehow made a difference, maybe lessen the loss of blood? What if he had pulled her from the car and jostled something vital, paralyzing her for life? Would he have received a phone call by now cursing him for his incompetence, blaming him for her wretched existence?

“Well?” Carrie yelled, impatient. “What’s going on?”

“It’s a girl,” Frank said. “She’s hurt. Bad.” He was grate- ful that the Camaro and the trees blocked Carrie’s view, grateful that she would not have to witness the girl’s suffering.

At the sound of his voice, the girl’s eyes popped open like an actress in a horror flick. “Hi,” he said, as if they were meeting at a cocktail party. He took one of her hands in his. She wore a silver ring on each finger, gypsyish, a peculiarity he imagined some boy in her life found endearing. Her hand was cold, limp. He rubbed it as if he were warming a child’s hand after a winter’s day outside. He whispered all the things he thought you were supposed to say when someone was in anguish. Then he said nothing.

It’s not quiet, death. Frank knows this now. Not like they tell you sometimes in books or on TV. Tales of people slipping from this world to the next like we slip in and out of clothes, just a change, another world, a light in a tunnel, perhaps, weightlessness, something like peace. The girl whispered things he never imagined himself whispering when he thought of his own death, something he had done compulsively in the year before he found her on that Halloween night in 1980. He imagined declarations, secrets revealed, illumination of spiritual truths. Instead, small things gurgled from her throat: the name of her kitten, the boy she had a crush on, the color of her bedroom. But it was not painless, the giving up of these details. She choked. She clawed. She wept.

“Whoa. That’s bad. She alive?”

Frank looked up to see a red-bearded man in a camouflage jacket standing over him. The man’s face was grooved, aged, the skin thick. Frank hadn’t noticed anyone approach. The man reached for the girl, put his finger against her neck. “She’s dead, sure enough. I already radioed in the accident, but I can’t be around when the cops get here.” The man turned, and without a backward glance, walked away.

All of it took maybe ten minutes.

After the man left, Frank could not seem to make himself walk back to the group he heard murmuring off in the distance. And then he thought, What if her parents had been notified? This was a small town. Many people had CB radios in their homes. What if her parents had heard the man call in the accident and recognized the description of the car? What if they were on their way to the scene right now? No parent should see a child like this.

He reached into the Camaro as best as he could and tugged at the hem of the girl’s leather dress, attempting to cover the white expanse of her thin thighs. He picked the leaves from her golden hair and smoothed it from her forehead, easing it behind ears studded with silver crosses, then decided that her hair would look better falling in soft waves around her face, so he arranged it that way. He licked his fingers, wiped the mud and streaks of blood from her cheeks, and marveled that there was hardly a scratch on her face, that the only visible injury appeared to be to her chest; and before he could stop himself, he reached for her wound, the exact point where the steering wheel had hit, and put his hand against her heart, perhaps not believing it could stop so easily.

She wore a gold locket, a delicate, heart-shaped thing, hard under his fingers, still warm with her body heat. He stared at it for a moment, flipping it over and over in his hand like a worry stone, studied the inscription on the back: On your sweet sixteen, Forever our baby girl. Still kneeling, he unhooked the locket from around her neck and wedged it into his pocket, wiping her blood on his jeans.

When Frank thinks of this moment now, he remembers that he saw everything by the light of the moon. But he wor- ries that he might have made parts of it up, and it’s a thing like getting something wrong that haunts him, not ever truly knowing what’s real and what’s not.

lll

Later, after they’d waited with the couple and their daughter for the ambulance and answered all the questions for the police, Frank and Carrie finally started the drive to their cabin for what they’d hoped would be a few days of quiet.

“You know what makes me sick?” Carrie said. “That drunk might as well have put a gun to that teenager’s head and shot her. And more than likely, nothing will happen to him.”

It was true. Back then, no one paid much attention to drunk drivers. Everyone carried coolers on their floorboards, wrapped beer cans in fake Coke covers as disguises. Frank had done it a hundred times, and he would do it again, although he told himself differently that night.

“And who would drive drunk with a beautiful little girl in the car?” Carrie said. “What kind of father would do that? What kind? They don’t deserve that little girl.”

Frank turned on the radio so he wouldn’t have to talk or think. An old country ballad about a man who drinks a woman up to a ten in a honky-tonk.

“You know what else?” Carrie said a few minutes later, turning down the radio. Her face shone in the moon’s glare. She was trying not to cry, something Frank wished he hadn’t noticed, because now he would have to deal with it, and he didn’t know how. Her voice lowered in a way that let Frank know she expected absolution. “I didn’t really want to touch that girl and woman because they were all covered in blood and I have on my new leather blazer. I didn’t want them to ruin it.” She began sobbing, pulling at her blazer, slapping her chest like a madwoman. “Can you believe that? What kind of person thinks that kind of thing?”

Then later, “Frank? Why does life have to be so relentlessly cyclical? Why can’t we move in some other direction? Why?”

lll

That Saturday at the cabin, Frank and Carrie sunbathed naked on their front porch, skinny-dipped in the chilly waters of the lake. They drank screwdrivers and daiquiris, danced to Pink Floyd and Lynyrd Skynyrd, and made love on the deck, on the boat, on the picnic table, anywhere that prohibited honest intimacy.

Neither Carrie nor Frank mentioned the accident, but it was there, always, the understanding of the brevity of things, the knowledge that there would be no eternity of lovemaking, of dancing drunkenly on the front porch. To Frank, it felt like a lie, this performance of carefree love, so he laughed the loudest, danced the longest, and reached for Carrie’s body as soon as his pulse slowed from their previous bout of lovemaking, telling himself there was only this, the here and now: Carrie’s mouth, Carrie’s thrumming heart.

Saturday evening, the night was unseasonably warm, the low-slung moon covered in clouds, and still half-drunk from sun and booze, they decided to grill steaks. Carrie wore only a bathrobe. She sat in a patio chair sipping a glass of wine, her heels cocked on the porch railing so that her satin robe spilled open. Her long legs, her breasts, the stretch of her neck, incandescent in the moonlight. Sitting as she was, staring into the distance, she seemed to Frank inaccessible and far away, a stranger, someone else’s wife, and he couldn’t quite remember how they’d gotten here, to this porch in Alabama, grilling steaks.

Carrie lit a cigarette, blew a delicate stream of smoke. “I’m not ovulating, you know. I just wanted you to know that. All the sex—it was just that. No ulterior motives.” She turned to him where he stood over the grill, nervously flipping the steaks from one side to the other, and waited.

“That’s good,” he said. “I appreciate that. You telling me.” But even as he said it, he worried that it wouldn’t be enough, that nothing he said would ever be enough again.

Carrie had miscarried at seven months, a baby haphazardly conceived one drunken night, a pregnancy that had launched their marriage into unexpected, terrifying territory. Carrie had been devastated by the loss. Partially, Frank suspected, because she had been slightly relieved when she miscarried and was horrified by her response.

After the funeral, things got ugly. They named the baby Mary Grace, and Carrie talked about her constantly, as though if she referenced Mary Grace enough, she could create a history for their daughter. The doctor gave Carrie pills to dry up her milk, but she wouldn’t take them, and for a week or so there were bottles and cans and bowls of pumped breast milk everywhere, the smell sour and intolerable. Carrie walked around the house in the dirty pink pajamas, her belly rounded, her hands cupped around her breasts. Watching her sit in the empty nursery in his grandmother’s rocking chair, a suction cup on her breast, her rocking and staring and crying, made Frank fist-through-the-wall angry. Not at Carrie, but at something he couldn’t put a name to, which made it even worse for her because she couldn’t tell the difference.

When the doctor gave them the thumbs-up a year ago, Carrie refused to discuss the possibility that maybe a baby was not the best thing with Frank just starting a new landscaping business. Instead, as if having a family had always been the plan, the miscarriage merely an obstacle, she began trying with the discipline of a soldier to get pregnant, and failed, and therefore was failing life in general, and because of this failure, resenting Frank. Frank, who had seemed untouched by the miscarriage, who had returned to work the next day, where he met with a carefully casual rich man in khakis to talk about how to landscape his summer home’s front yard, how to make it a work of art.

But Carrie was mellow tonight, introspective and thoughtful, and she did not attack Frank, just sat and smoked and watched the cloud-muted moon heft itself into the vault of the sky.

“Why don’t you grab a plate?” Frank asked. “I think these are almost ready.” He wore his Kiss the Cook apron, big red lips seared across his abdomen. He puckered his own mouth at Carrie, and she waved her hand at him to stop.

“Do you wonder about her?” Carried asked, not moving toward the kitchen. She crushed out her cigarette, fumbled with the pack, then pulled out another and lit it. “Who she was? What she wa...

“Look, Frank, trick-or-treaters,” Carrie said, breaking the silence of the last half hour. “What are they doing all the way out here?”

“Here” was a country back road, eastern Alabama. Halloween, 1980.

“Those aren’t trick-or-treaters,” Frank said, easing the truck onto the sandy shoulder of the road. Up ahead, flipped on its side, half on the shoulder and half in the ditch, was a red-and-white-striped GMC Jimmy, one taillight blinking off and on, a maniacal, fluttering eye. Behind them, perhaps twenty feet, a knot of people huddled on the side of the road, not moving.

“Maybe we should drive on to the bait shop,” Frank said. “Call the police from the pay phone.” He had heard stories of people faking accidents in order to rob or rape unsuspecting Good Samaritans, and he couldn’t help but wonder if this was it, the night a knife slid across his throat or, worse, Carrie’s. The night everything was written out for them. The next morning, a work crew or a vagrant searching for aluminum cans would find their naked bodies on the side of the road, half-covered in wet pine needles, red clay.

“What’s your problem?” Carrie snapped. She opened her door, slid from the truck. “They might be hurt. Don’t just sit there.”

The first thing he noticed when he opened his own door was the smell, hovering and sweet, like just bloomed honeysuckles. That mixed with gasoline and burnt rubber.

“Are y’all all right?” Carrie half yelled at the still unmoving knot behind them, but she stayed close to the truck.

A man, maybe forty, with pulpy, torn lips, finally loped over, extending his hand to Frank in a strange semblance of formality. He had hair cropped so short it had no color, light eyes to match. He wore an unbuttoned Hawaiian covered with little monkeys surfing. Behind him trailed a young woman and a small girl, just past toddler. Both of their faces were pretty banged up. They rushed toward Carrie as though they knew her, began clutching at her arms in a panic until Carrie awkwardly embraced them.

“You’re the third car to come through here,” the man said, grinding the heels of his boots into the grainy road. “No one else would stop. No one. Who could see two hurt girls and keep going?” He tugged a hand through his short hair, revealing a bloody forehead. “I just don’t get it anymore, man. The big IT. You know what I mean?” He began crying, heaving gasps that horrified Frank. The man was shit-faced.

The woman had two-toned hair the yellow and copper of poor white, and she wailed in response, pressed her face against Carrie’s leather jacket. “I think they’re more scared than hurt,” Carrie said to no one in particular.

When the man reached for his wife, she pulled away. “My face, you idiot.” Her fingers moved over her cheeks as if she could piece it back together. “I’ve told you a thousand times. A thousand. Slow. Down.” The little girl clamped her eyes shut and didn’t make a sound. She wore a striped leotard, one foot bare, the other in a tiny ballet slipper, the remnants of her Halloween costume, a bumblebee.

“That car flew out of fucking nowhere,” the man said, suddenly angry. When he yelled, he sprayed blood instead of spit. He slammed a fist into his palm. “Nowhere.” His wife and kid tried to burrow holes into Carrie with their faces; they seemed familiar with his anger.

“What car?” Frank said. He’d assumed that it was a one-car accident, a drunk man overcompensating for veering off the road, something anyone could do, including Frank, who’d had a beer or two himself that night.

The man pointed behind them, into the fringe of woods off the oncoming lane.

“You checked it out?” Frank asked. The man stared at his boots, shook his head no. The woman began whimpering, soft and wet.

Frank looked to where the man had pointed. There, some fifty feet away, as bright as the harvest moon that lit the night, was a yellow Camaro, its front crushed against an oak like crumpled paper. Glass and bits of metal glittered against the asphalt. There was no reasonable explanation for how he could have not noticed it until that moment, and he could hear the refrain Carrie had been saying lately: You only see what you want to see, Frank. That’s your problem.

“You stay here,” Frank said to Carrie. “Wave anyone down who passes. Ask if they have a CB radio.”

It’s strange, but on his walk over to the Camaro, this was what he thought: What a lovely night! How could anything so violent happen on such a night? It was still and pleasant, warm for late October, and if he tilted his head back, he could see nothing but blue-black and stars. When he approached the car, he saw a teenage girl in a black leather dress, the bottom half of her body still in the driver’s seat, her trunk slung out the opened door into the thick brush, her long blond hair tangled with debris, her face pale and still as the night. In such a dramatic position, she was bizarrely beautiful.

The girl looked dead, but to be sure, he knelt, placed his finger against her neck for a pulse. Her skin felt silky, soft. From the looks of her, she was the kind to pamper it, to spread creamy lotion over her neck, arms, elbows, chest. He held his finger there for a full minute before he felt a flicker, soft as eyelashes.

Frank cannot help but ask himself now, Should he have pulled her from the car? Would it have somehow made a difference, maybe lessen the loss of blood? What if he had pulled her from the car and jostled something vital, paralyzing her for life? Would he have received a phone call by now cursing him for his incompetence, blaming him for her wretched existence?

“Well?” Carrie yelled, impatient. “What’s going on?”

“It’s a girl,” Frank said. “She’s hurt. Bad.” He was grate- ful that the Camaro and the trees blocked Carrie’s view, grateful that she would not have to witness the girl’s suffering.

At the sound of his voice, the girl’s eyes popped open like an actress in a horror flick. “Hi,” he said, as if they were meeting at a cocktail party. He took one of her hands in his. She wore a silver ring on each finger, gypsyish, a peculiarity he imagined some boy in her life found endearing. Her hand was cold, limp. He rubbed it as if he were warming a child’s hand after a winter’s day outside. He whispered all the things he thought you were supposed to say when someone was in anguish. Then he said nothing.

It’s not quiet, death. Frank knows this now. Not like they tell you sometimes in books or on TV. Tales of people slipping from this world to the next like we slip in and out of clothes, just a change, another world, a light in a tunnel, perhaps, weightlessness, something like peace. The girl whispered things he never imagined himself whispering when he thought of his own death, something he had done compulsively in the year before he found her on that Halloween night in 1980. He imagined declarations, secrets revealed, illumination of spiritual truths. Instead, small things gurgled from her throat: the name of her kitten, the boy she had a crush on, the color of her bedroom. But it was not painless, the giving up of these details. She choked. She clawed. She wept.

“Whoa. That’s bad. She alive?”

Frank looked up to see a red-bearded man in a camouflage jacket standing over him. The man’s face was grooved, aged, the skin thick. Frank hadn’t noticed anyone approach. The man reached for the girl, put his finger against her neck. “She’s dead, sure enough. I already radioed in the accident, but I can’t be around when the cops get here.” The man turned, and without a backward glance, walked away.

All of it took maybe ten minutes.

After the man left, Frank could not seem to make himself walk back to the group he heard murmuring off in the distance. And then he thought, What if her parents had been notified? This was a small town. Many people had CB radios in their homes. What if her parents had heard the man call in the accident and recognized the description of the car? What if they were on their way to the scene right now? No parent should see a child like this.

He reached into the Camaro as best as he could and tugged at the hem of the girl’s leather dress, attempting to cover the white expanse of her thin thighs. He picked the leaves from her golden hair and smoothed it from her forehead, easing it behind ears studded with silver crosses, then decided that her hair would look better falling in soft waves around her face, so he arranged it that way. He licked his fingers, wiped the mud and streaks of blood from her cheeks, and marveled that there was hardly a scratch on her face, that the only visible injury appeared to be to her chest; and before he could stop himself, he reached for her wound, the exact point where the steering wheel had hit, and put his hand against her heart, perhaps not believing it could stop so easily.

She wore a gold locket, a delicate, heart-shaped thing, hard under his fingers, still warm with her body heat. He stared at it for a moment, flipping it over and over in his hand like a worry stone, studied the inscription on the back: On your sweet sixteen, Forever our baby girl. Still kneeling, he unhooked the locket from around her neck and wedged it into his pocket, wiping her blood on his jeans.

When Frank thinks of this moment now, he remembers that he saw everything by the light of the moon. But he wor- ries that he might have made parts of it up, and it’s a thing like getting something wrong that haunts him, not ever truly knowing what’s real and what’s not.

lll

Later, after they’d waited with the couple and their daughter for the ambulance and answered all the questions for the police, Frank and Carrie finally started the drive to their cabin for what they’d hoped would be a few days of quiet.

“You know what makes me sick?” Carrie said. “That drunk might as well have put a gun to that teenager’s head and shot her. And more than likely, nothing will happen to him.”

It was true. Back then, no one paid much attention to drunk drivers. Everyone carried coolers on their floorboards, wrapped beer cans in fake Coke covers as disguises. Frank had done it a hundred times, and he would do it again, although he told himself differently that night.

“And who would drive drunk with a beautiful little girl in the car?” Carrie said. “What kind of father would do that? What kind? They don’t deserve that little girl.”

Frank turned on the radio so he wouldn’t have to talk or think. An old country ballad about a man who drinks a woman up to a ten in a honky-tonk.

“You know what else?” Carrie said a few minutes later, turning down the radio. Her face shone in the moon’s glare. She was trying not to cry, something Frank wished he hadn’t noticed, because now he would have to deal with it, and he didn’t know how. Her voice lowered in a way that let Frank know she expected absolution. “I didn’t really want to touch that girl and woman because they were all covered in blood and I have on my new leather blazer. I didn’t want them to ruin it.” She began sobbing, pulling at her blazer, slapping her chest like a madwoman. “Can you believe that? What kind of person thinks that kind of thing?”

Then later, “Frank? Why does life have to be so relentlessly cyclical? Why can’t we move in some other direction? Why?”

lll

That Saturday at the cabin, Frank and Carrie sunbathed naked on their front porch, skinny-dipped in the chilly waters of the lake. They drank screwdrivers and daiquiris, danced to Pink Floyd and Lynyrd Skynyrd, and made love on the deck, on the boat, on the picnic table, anywhere that prohibited honest intimacy.

Neither Carrie nor Frank mentioned the accident, but it was there, always, the understanding of the brevity of things, the knowledge that there would be no eternity of lovemaking, of dancing drunkenly on the front porch. To Frank, it felt like a lie, this performance of carefree love, so he laughed the loudest, danced the longest, and reached for Carrie’s body as soon as his pulse slowed from their previous bout of lovemaking, telling himself there was only this, the here and now: Carrie’s mouth, Carrie’s thrumming heart.

Saturday evening, the night was unseasonably warm, the low-slung moon covered in clouds, and still half-drunk from sun and booze, they decided to grill steaks. Carrie wore only a bathrobe. She sat in a patio chair sipping a glass of wine, her heels cocked on the porch railing so that her satin robe spilled open. Her long legs, her breasts, the stretch of her neck, incandescent in the moonlight. Sitting as she was, staring into the distance, she seemed to Frank inaccessible and far away, a stranger, someone else’s wife, and he couldn’t quite remember how they’d gotten here, to this porch in Alabama, grilling steaks.

Carrie lit a cigarette, blew a delicate stream of smoke. “I’m not ovulating, you know. I just wanted you to know that. All the sex—it was just that. No ulterior motives.” She turned to him where he stood over the grill, nervously flipping the steaks from one side to the other, and waited.

“That’s good,” he said. “I appreciate that. You telling me.” But even as he said it, he worried that it wouldn’t be enough, that nothing he said would ever be enough again.

Carrie had miscarried at seven months, a baby haphazardly conceived one drunken night, a pregnancy that had launched their marriage into unexpected, terrifying territory. Carrie had been devastated by the loss. Partially, Frank suspected, because she had been slightly relieved when she miscarried and was horrified by her response.

After the funeral, things got ugly. They named the baby Mary Grace, and Carrie talked about her constantly, as though if she referenced Mary Grace enough, she could create a history for their daughter. The doctor gave Carrie pills to dry up her milk, but she wouldn’t take them, and for a week or so there were bottles and cans and bowls of pumped breast milk everywhere, the smell sour and intolerable. Carrie walked around the house in the dirty pink pajamas, her belly rounded, her hands cupped around her breasts. Watching her sit in the empty nursery in his grandmother’s rocking chair, a suction cup on her breast, her rocking and staring and crying, made Frank fist-through-the-wall angry. Not at Carrie, but at something he couldn’t put a name to, which made it even worse for her because she couldn’t tell the difference.

When the doctor gave them the thumbs-up a year ago, Carrie refused to discuss the possibility that maybe a baby was not the best thing with Frank just starting a new landscaping business. Instead, as if having a family had always been the plan, the miscarriage merely an obstacle, she began trying with the discipline of a soldier to get pregnant, and failed, and therefore was failing life in general, and because of this failure, resenting Frank. Frank, who had seemed untouched by the miscarriage, who had returned to work the next day, where he met with a carefully casual rich man in khakis to talk about how to landscape his summer home’s front yard, how to make it a work of art.

But Carrie was mellow tonight, introspective and thoughtful, and she did not attack Frank, just sat and smoked and watched the cloud-muted moon heft itself into the vault of the sky.

“Why don’t you grab a plate?” Frank asked. “I think these are almost ready.” He wore his Kiss the Cook apron, big red lips seared across his abdomen. He puckered his own mouth at Carrie, and she waved her hand at him to stop.

“Do you wonder about her?” Carried asked, not moving toward the kitchen. She crushed out her cigarette, fumbled with the pack, then pulled out another and lit it. “Who she was? What she wa...

Le informazioni nella sezione "Su questo libro" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

- EditoreRandom House Trade Paperbacks

- Data di pubblicazione2007

- ISBN 10 0812973526

- ISBN 13 9780812973525

- RilegaturaCopertina flessibile

- Numero di pagine208

- Valutazione libreria

Compra nuovo

Scopri di più su questo articolo

EUR 17,90

Spese di spedizione:

GRATIS

In U.S.A.

I migliori risultati di ricerca su AbeBooks

Our Former Lives in Art: Stories

Editore:

Random House Trade Paperbacks

(2007)

ISBN 10: 0812973526

ISBN 13: 9780812973525

Nuovo

Brossura

Quantità: 1

Da:

Valutazione libreria

Descrizione libro Condizione: New. . Codice articolo 52GZZZ016GPO_ns

Compra nuovo

EUR 17,90

Convertire valuta

OUR FORMER LIVES IN ART: STORIES

Editore:

Random House Trade Paperbacks

(2007)

ISBN 10: 0812973526

ISBN 13: 9780812973525

Nuovo

Brossura

Quantità: 1

Da:

Valutazione libreria

Descrizione libro Condizione: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.5. Codice articolo Q-0812973526

Compra nuovo

EUR 71,55

Convertire valuta