Articoli correlati a Zoli: A Novel

Le informazioni nella sezione "Riassunto" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

A dog, all bones and scars, noses out in front of the car, and within moments the dog has brought children, crowding up against the car windows. He tries nonchalance as he snaps down the locks with his elbow. One boy is agile enough to jump onto the hood with hardly a noise—he grabs the windshield wipers and spreads himself out. A cheer goes up as two other kids take hold of the bumper and skate behind on the bare soles of their feet. Teenage girls jog alongside in their low-slung jeans. One of them points and laughs, but then stops, still, silent. The boy slides off the hood and the skating kids let go of the bumper, and suddenly the river is in front of him, swirling, fast, brown, unexpected. He yanks the steering wheel hard. Brambles scrape the windows. Tall grass crunches under the wheels. The car swerves back towards the mudtrack, and the children run alongside again in uproar.

On the far bank two old women stand up from where they’re washing bedsheets using riverrock and lye. They shake their heads, half-smile, and stoop once more to their work.

He steers around another tight corner, towards a blind line of trees, past the remains of a shattered lettuce crate in the long grass, and there, across a rickety little joke of a bridge, is the gray Gypsy settlement, marooned on an island in the middle of the river, as if the water itself has changed its mind and flowed either side. Shanty houses. Windowless huts. Jagged pipes and mismatched wood. Thin scarves of smoke rising up from the chimneys. Each roof pockmarked with a satellite dish and patched with scraps of corrugated iron. Far off in the distance a single blue coat flaps in the branches of a tree.

He guides the car into the long weeds, stops, pulls the handbrake, takes a second to pretend that he’s looking for something in the glovebox, searches deep, though there’s nothing there, not a thing, just a chance to get a small respite. The children crowd the windows. He pushes open the car door, and all he can hear from the settlement across the water is a dozen radios blaring all at once, songs Slovakian and American and Czech.

Instantly the children thumb his sleeve, knuckle his ribcage, pat his jacket pockets. It’s as if he has become a dozen hands all at once. “Quit!” he shouts, swatting them away. One boy hops on the front bumper so that the whole car bows to the rhythm. “Okay,” he shouts, “enough!” The older teenagers in dark leather jackets shrug. The girls in unbuttoned blouses step back and giggle. How immaculate their teeth. How quick the silver of their pupils. The tallest of the boys steps forward in a muscle-shirt. “Robo,” the boy says, puffing out his chest. They shake hands and he pulls the boy aside, has a word, face close to his ear. He tries to block the deep smell of the boy, wet wool and raw smoke, and within seconds a deal is struck—fifty krowns—to bring him to the elders and to keep the car safe.

Robo shouts out a warning to the others, backhands the child who is tiptoe on the rear bumper. They make their way towards the bridge. More children arrive from along the river, some naked, some in diapers, one in a torn pink dress and flip-flops, and the same girl seems to appear from all angles, but in different shoes each time; beautiful, coal-eyed, hair uncombed.

He watches the kids cross the bridge like a strange line of herons, one foot heavy on the solid planks, high-toed and light on the rest. The metal sheets vibrate under their weight. He totters a moment on a piece of plyboard, sways, reaches for a hold, but there is none. The children put their hands to their mouths and snigger—he is, he thinks, every idiot who has ever walked this way. He feels the weight of what he carries: two bottles, notepad, pencil, cigarettes, camera, and tiny recorder, all hidden away deep in his clothes. He pulls the jacket tight and leaps the final hole in the bridge, lands in the soft mud on the far side, just twenty yards from the shanties. He looks up, takes a deep breath, but it’s as if a thousand chords have been struck all at once, his ribcage is thumping, he shouldn’t have come here alone, a Slovakian journalist, forty-four years old, comfortably fat, a husband, a father, about to step into the heart of a Gypsy camp. He takes a step forward through a puddle, thinking how stupid it was to wear soft leather shoes for this trip, not even good for a quick retreat.

At the edge of the shacks he becomes aware of the brooding men leaning against woodpole doorways. Women stand with hands folded across their stomachs. He tries to catch their gaze, but they look beyond him and away with thousand-yard stares. Strange, he thinks, that they do not question him; maybe they’ve mistaken him for a policeman or a social worker or a parole officer or some other government fuckwad here on an official visit.

He feels briefly powerful as Robo leads him deeper into the warren of mudroutes.

Doorframes used as tables. Sackcloth for curtains. Empty ?cu?cu bottles strung up as windchimes. At his feet, bits of wood and porridge containers, lollipop sticks and shattered glass, the ground-down bones of some dead animal. He catches glimpses of babies hammocked from ceilings, flies buzzing around them as they sleep. He reaches for his camera but is pushed on in the swell of children. Open doorways are quickly closed. Bare bulbs switched off. He notices carpets on the walls, and pictures of Christ, and pictures of Lenin, and pictures of Mary Magdalene, and pictures of Saint Jude lit by small red candles high above empty shelves. From everywhere comes the swell of music, no accordions, no harps, no violins, but every shack with a TV or a radio on full volume, an endless thump.

Robo leans over and shouts in his ear, “Over here, Uncle, follow me,” and it strikes him how foreign this boy, how distant, how dark-skinned.

He is led around a sharp corner to the largest shanty of all. A satellite dish sits new and shiny on the roof. He knocks on the plywood door. It swings open a little further with each knuckle rap. Inside there is a contingent of eight, nine, maybe ten men. They raise their heads like a parliament of ravens. A few of them nod, but they continue their hand, and he knows the game is nonchalance—he has played it himself in other parts of the country, the flats of Bratislava, the ghettos of Pre?sov, the slums of Letanovce.

In the far corner of the room he notices two women watching him, wide-eyed. A hand pushes him at the small of his back. “I’ll wait for you here, mister,” says Robo, and the door creaks behind him.

He looks around the room, the immaculate floor, the ordered cupboards, the whiteness of the one shirt hanging on a nail from the ceiling.

“Nice house,” he says, and knows immediately how foolish it sounds. He flushes red-cheeked, then draws himself tall. In the corner sits a broad-shouldered man, tough, hard-jawed, gray hair tousled after a bad night’s sleep. He steps across and announces quite softly that he’s a journalist, he’s here on a story, he’d like to talk to some of the old folk.

“We’re the old folk,” says the man.

“Right,” he says, and pats his jacket. He fumbles in his pocket and breaks open a pack of Marlboros. Stupid, he knows, not to have broken the seal already. In the silence the others watch him. His hands shake. A bead of sweat runs down his brow. He can almost hear the chest hair rustle under his shirt. He unwinds the plastic, lifts the cellophane, and shoves three cigarettes up like peeping toms.

“Just want to talk,” he says.

The man waits for a light, blows the smoke sideways.

“About what?”

“The old days.”

“Yesterday was long,” says the man with a laugh, and the laughter ripples around the room, tentatively at first, until the women catch it and it builds, unraveling the tension. He is suddenly slapped on the shoulder and his grin breaks wide, and the men start to talk in an accent that starts low and ends high, musical, fast, jangly. Some of the words appear to be in Romani, and from what he can make out, the man’s name is Boshor. He reaches past Boshor, throws the cigarettes on the table, and the men casually reach for them. The women step across, one of them suddenly young and beautiful. She bends for a light, and he looks away from the low swing of her breasts. Boshor points to the cards and says: “We’re playing for a little food, a little drink too.” The man pulls again on the cigarette. “We’re not really drinkers, though.”

He takes his cue from Boshor, opens a button, slips back his shirtfront, exposing his flabby chest, and removes the first bottle like a trophy. Boshor picks up the bottle, turns it in his hands, nods approval, and rattles off a salvo of Romani to more laughter.

He watches as the young girl reaches into a cupboard. She takes down a mahogany box with a silver clasp, opens it wide. A matching set of china cups. She puts them on the table, unscrews the bottle. He is given, he notices, the only china cup that is not chipped.

Boshor leans back and gently says: “Health.”

They clink cups, and Boshor leans forward to whisper: “Oh, it’s for money too, friend. We’re playing cards for money.”

He doesn’t even flinch; he slaps down two hundred krowns. Boshor takes it, slips it into his trousers, smiles, blows smoke towards the ceiling.

“Thank you, friend.”

The cards are put aside, and the drinking starts in earnest. He is amazed how close Boshor sits t...

Le informazioni nella sezione "Su questo libro" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

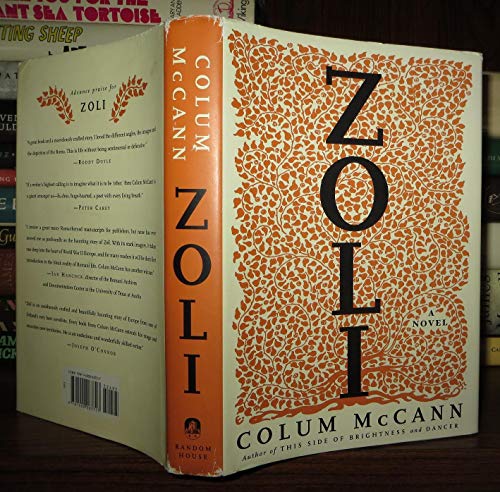

- EditoreRandom House Inc

- Data di pubblicazione2007

- ISBN 10 1400063728

- ISBN 13 9781400063727

- RilegaturaCopertina rigida

- Numero di pagine333

- Valutazione libreria

Compra nuovo

Scopri di più su questo articolo

Spese di spedizione:

EUR 3,69

In U.S.A.

I migliori risultati di ricerca su AbeBooks

Zoli: A Novel

Descrizione libro Hardcover. Condizione: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Codice articolo Holz_New_1400063728

Zoli: A Novel

Descrizione libro Hardcover. Condizione: new. Brand New Copy. Codice articolo BBB_new1400063728

Zoli: A Novel

Descrizione libro Hardcover. Condizione: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Codice articolo GoldenDragon1400063728

Zoli: A Novel

Descrizione libro Hardcover. Condizione: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Codice articolo think1400063728

ZOLI: A NOVEL

Descrizione libro Condizione: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.07. Codice articolo Q-1400063728